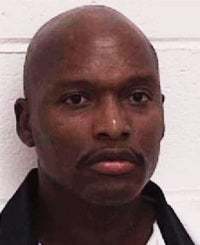

As those who have followed the news lately are no doubt aware, a federal appeals court yesterday issued a stay postponing my execution by the state of Georgia. In the wake of this development, capital punishment advocates around the country have voiced their collective outrage over the deferment of my sentence, calling for the state-mandated death of me, Warren Lee Hill, a mentally retarded man.

However, should the authorities go through with this killing, I contend it would be a moral aberration without parallel. Truly, the state-enforced execution of a mentally challenged individual such as myself runs contrary to every humanitarian principle upon which our society is built.

Setting aside the moral complexities that invariably accompany the death penalty—itself a thorny ethical issue—let me remind you that the convicted man in this case is myself, an intellectual infant with an insurmountable cognitive handicap. Every medical expert who has evaluated my condition has concluded, with total certainty, that my diminished cerebral capacity leaves me woefully unable to participate in society in any meaningful way. By my own admission, I lack the capacity for the most basic of mental functions, including reasoning, memory, and, most critically, the ability to discern right from wrong.

And so I put it to you, reader: Can a veritable man-child such as myself truly be held accountable for his actions?

Nonetheless, those who have called for my execution paint me as a beast. They depict a twice-convicted killer who supposedly was fully aware of the nature of his crimes and who, despite his woefully insufficient mental faculties, deserves nothing more than to be put down like a rabid dog. Granted, the nature of my alleged crimes was brutal, and the question of my culpability is no easy issue. On the contrary, it is a moral quandary whose depth even I, as a mentally retarded man with the logic and reasoning capabilities of a child, can appreciate.

However, at its heart, what we are looking at is the question of whether someone such as myself, whose intelligence quotient of 70 scarcely registers above that of a toddler’s, can truly be held responsible for his actions. After all, I am someone who has no awareness of the nature of his crimes, no ability to comprehend the feelings of others, and only the slightest conception of the consequences of my actions. Why, I am barely able to speak in coherent sentences, let alone grasp the intricacies of modern jurisprudence.

Furthermore, if we are to briefly set aside the fundamental moral implications of a state putting to death a mentally impaired person—namely me—then we still have not yet even considered the clear-cut legal precedents established by our nation’s judicial system. Indeed, the U.S. Supreme Court in 2002 established conclusively in Atkins v. Virginia that the use of the death penalty against the retarded constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment” as expressly barred by the Eighth Amendment. The legal underpinnings of the issue could not be more conclusive.

Even I can see that.

But, aside from these labyrinthine legal matters, the question of whether to end the life of me, a helplessly disabled man with at best a rudimentary, infant-like understanding of right and wrong, is inherently a moral issue. After all, what kind of society are we if we are willing to put a permanent end to the life of a helpless, intellectually feeble man such as myself? How would the carrying out of such an execution reflect on us, on our basic human decency? After all, as Mohandas Gandhi himself said, “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” As a proud democracy, we should hold ourselves to no less exacting a standard.

Thank you.