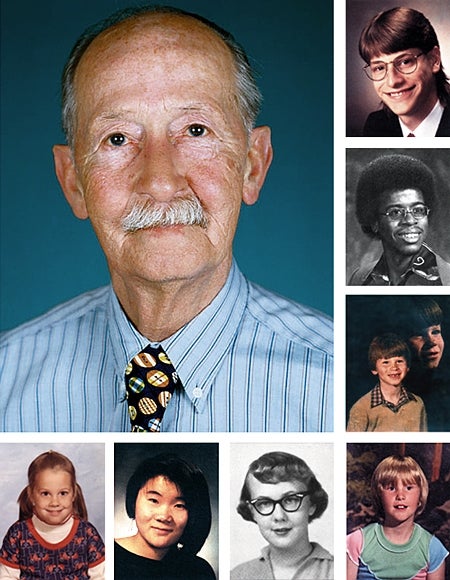

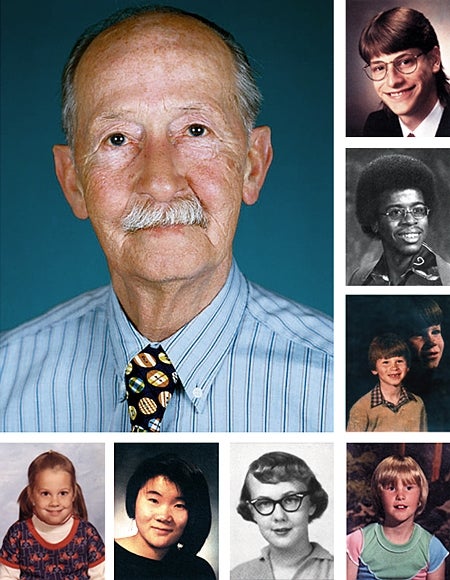

PHOENIX—Henry Anszczak, the photographer whose influential work revolutionized modern school portraiture, died Sunday at his family home in Eloy. He was 92.

According to longtime assistant Dave Olsen, Anszczak died of natural causes.

“On Sunday, Mr. Anszczak passed away peacefully in his sleep, surrounded by his family and scores of yearbooks,” Olsen said. “We will never forget his wonderful artistic achievements. He blazed the trail for thousands of school photographers nationwide. The lion of 20th-century public-educational culture roars no more.”

Anszczak’s innovations became so much a part of the language of school portraiture that their brilliance is often overlooked.

“Anszczak was the first to present his subjects as individuals, rather than as one tiny, grainy part of the class as a whole,” said Geraldine Menzies, director of the National Academy of Classroom Arts in Philadelphia, where many of Anszczak’s works are exhibited. “He lifted the school-portrait camera from its rigid confines and moved it several feet closer.”

Fresh out of the Army in 1946, armed with a Graflex Speed Graphic camera and a tripod, Anszczak began his school-photography career relatively late in life. The 34-year-old entered a stagnant field, where the standard practice of shooting black-and-white snapshots of entire classes from a distance had gone unquestioned for decades. While it saved on film and developing costs, the process resulted in a final portrait in which many subjects were out of focus, too small to see, or obscured altogether. When Anszczak retired in 1986, he left a field that had fully embraced his color close-ups and woodland backdrops.

This sea change eliminated the process, considered tedious by photographers and teachers alike, of assembling a class as a whole. Anszczak’s innovation also eliminated the problem of group photos ruined by absenteeism and individual students’ antics, such as goofy expressions or inappropriate hand gestures.

Anszczak is credited with having invented the classroom composite, in which many small, rectangular portraits are arranged in rows for display.

“Anszczak single-handedly standardized the wallet-size,” Menzies said. “It was his discovery that, in addition to a 5″x7″ portrait suitable for framing, a student might like a number of smaller photos to offer to those peers with whom he or she plans to remain best friends forever.”

Anszczak was the first school photographer to offer matte finish. He was the first to seat subjects on a stool, to direct them in proper placement of their hands, and to offer them the use of a black plastic comb before the photo was taken. He pioneered use of soft-focus, previously seen only in Hollywood glamour portraits, in senior-year photos. And he introduced the now-famous “fence post, wagon wheel, and bale of hay” tableau, which became an industry standard.

“Scholars debate whether it was Anszczak or his assistant who invented the double-exposure, in which a profile of the student’s face appears over the shoulder of the forward-facing subject,” Menzies said. “But there is no question that they were the first to use the technique in the portable studio.”

Anszczak’s innovations, now universally accepted, were initially criticized. Parents thought that the individual close-ups bore an uncomfortable similarity to police mug shots. Additionally, many argued that the process of focusing so closely on the subject placed students under undue stress.

Following the Vietnam war, a new batch of critics argued that Anszczak’s work had reactionary, antisocial tendencies. In a famous essay for Mrs. Larsen’s tenth-grade English class at Sherman High School in Little Rock, AR, sophomore Wayne Kleiff derided the photographer’s individual portraits as “a physical manifestation of the isolation produced from postwar suburbanization.”

“Before Anszczak, the individual was represented as part of a whole,” wrote Kleiff, ’78. “What’s missing from Anszczak’s work is a sense of community, of people mutually sharing a social and educational experience. Is it any coincidence that he and suburbia mushroomed together? Like the white picket fence around a single-story frame home, the white borders in Anszczak’s composite photos serve to separate, to isolate, to detach. At their worst, they promote narcissism and insularity.”

Kleiff’s composition received an A.

Anszczak’s fans, however, laud the spontaneity of his work. In spite of the controlled conditions in a school’s cafeteria or gymnasium on photo day, imperfections would occur. Anszczak resolutely refused to do retakes.

“Look at these superb Anszczaks here,” said Dorian Childsworth, a photography historian at George Eastman House in Rochester, NY, as she gestured at an open portfolio of portraits. “Observe the immediacy of his work. We see closed eyes, drifting gazes, unattractively agape mouths, tucked-in collars, and hair sticking up all funny. But Anszczak did not weed such imperfections out. He embraced them. In so doing, he captured the awkward hearts and souls of these individuals. These photos show an intuitive sympathy at work—the mark of a true artist.”

“Rest in peace, Mr. Anszczak,” Childsworth added. “Or, in your words, ’Say cheeseburger.’”

After an incredible 40-year career, Anszczak rejected photography in 1986 to pursue “purer artistic pursuits that more actively engage the mind’s eye.” In this late period, he designed yearbook covers and lunchroom murals.

Still, Anszczak will be remembered best for his widely emulated school portraiture. Fittingly, school districts across the country lowered their flags to half-staff in honor of Anszczak on the day following his death. In addition, the International League of Hot Lunch Workers Monday announced plans to rename fruit-cocktail cups “Henrys.”