The year was 1987, a time I’ll never forget. The country was in the grips of the Great Recession, the worst economic crisis my generation had ever known. In October of that year, the bottom fell out of the market, tumbling a record 508 points in a single day. Back then I was green as hell, working with discretionary accounts at Tanner & Reamish with little more to show for myself than an office overlooking Wall Street and a few hundred thou in convertible securities. But I found out real quick what life was like back in ’87.

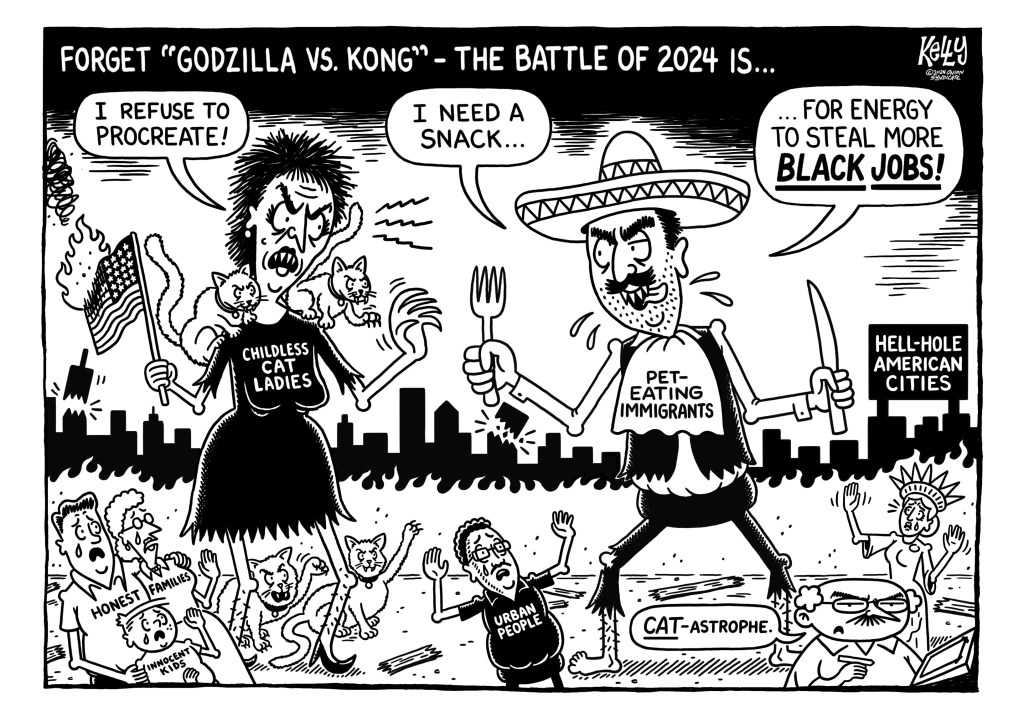

People were doing anything they could to get by. I saw grown men working blue-collar construction jobs, just to feed their families. I saw people buying used cars. In New York City, people were selling pretzels on the street for a buck-fifty, a buck—anything they could get. It was horrible.

I still vividly recall October 19 of that year, the day ever to be remembered as Black Monday. A black day indeed. That was the day the market plummeted those 508 points. The bull market had turned on us, and everything seemed to dispute the invincibility of my colleagues and myself. That was too much for any of us to bear. Many a good broker was sent right over the edge. How was I going to make it through? What about the wife, the kids, the money market funds? Thank God I had 550 shares of gilt-edged stock in a blue chip tucked away for a rainy day.

Things were hard at home. When we reached the third week of the recession, we knew we were in for a long haul, maybe months of hardship. We faced the choice of either giving up the lease on the golf course or nixing my teenage daughter’s plans for summer weight-loss camp in France—a decision no one should ever have to face. We’d already stopped getting the pool cleaned altogether. What more could we do?

It was during the Recession of ’87 that I found out what hunger really was. When times got tough I gave up my daily lunch at Geraldine’s and started to order food in. I would eat anything just to cut the hunger—sweet-and-sour pork that came in the strangest little white and red boxes, Greek salads that came with plastic forks and paper napkins. Even “sandwiches,” like the ones my nanny made me as a child.

The delivery boys were sometimes as much as 45 minutes late. Once I waited over an hour for lunch. But you know what? I still tipped that little delivery guy. I remember saying as I flipped him a shiny 50-cent piece, “We’ll all learn a lesson from this adversity. Chin up!” There was an unreadable look of pain on his face as he put the money in his uniform pocket and loaded his heavy, insulated pack onto his shoulder.

That’s what was beautiful about the Recession—people banded together. Even though you were barely making it, you helped out someone who might have less than you. If you heard about a high premium or a new tax shelter, if it didn’t affect your own convertible securities you’d give that information to anyone who needed it.

During the fourth week, though, when the fear began to set in, I had to let the chauffeur and the gardener go at the house. They’d been with us for 11 years, but necessity forced us to replace them with temp-agency workers. It was terribly hard for me to tell Darryl and Ramon to pack their bags, but like I said, those were hard times. I did things that were hard.

Those of us who struggled through the Recession are often portrayed today as “stingy” or “tight-fisted.” Jokes are made about how we’re still obsessed. Hogwash! Young people today don’t understand the meaning of the word poor, the word fear, the word fiduciary. If they did, they’d take my advice and disperse their investments in Keough plans and zero-coupon bonds and they’d oppose those new-fangled ’90s ideas like capital gains taxes, AFDC and Medicare. They’d also make sure they had enough suits to go three months without dry cleaning, because when times are tight, every dollar counts.